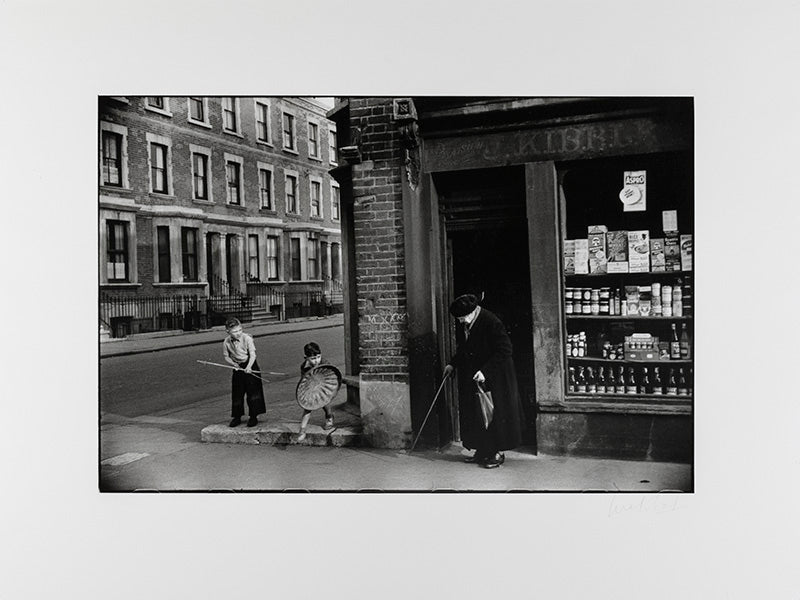

Marc Riboud

Greenwich, England by Marc Riboud

Toronto, ON)

Toronto, ON)

Learn about our Shipping & Returns policy.

Have a question? Read our FAQ.

- Artwork Info

- About the Artist

-

1954

Gelatin silver print

Signed, in pencil, au recto

Titled and dated, in pencil, with artist stamp, in ink, au verso

Printed circa 1980

Unframed -

Marc Riboud (1923-2016) took his first photograph in 1937 at the Exposition Universelle in Paris using a small Kodak camera he received as a birthday gift from his father. Following World War II, where he was active in the French resistance movement, Riboud studied engineering before determining to dedicate himself to photography. He would go on to capture moments of grace even in the most fraught situations around the world.

Riboud’s career of more than 60 years carried him routinely to turbulent places throughout Asia and Africa in the 1950s and ’60s, but he may be best remembered for two photographs taken in the developed world. The first, from 1953, is of a workman poised like an angel in overalls between a lattice of girders while painting the Eiffel Tower — one hand raising a paintbrush, one leg bent in a seemingly Chaplinesque attitude. The second, from 1967, is of a young woman presenting a flower to a phalanx of bayonet-wielding members of the National Guard during an anti-Vietnam War demonstration at the Pentagon. Both images were published in Life magazine during what is often called the golden age of photojournalism, an era Riboud exemplified.

A protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Riboud was on the front lines of world events, including wars. Even so, he did not consider himself a record keeper. “I have shot very rarely news,” Riboud once said. Rather than portray the military parades or political leaders of the Soviet Union, for example, he was drawn to anonymous citizens sitting in the snow, holding miniature chess boards and absorbed in their books. Of the many hundreds of shots he published from Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Pakistan, Tibet and Turkey, only a handful are of figures written about by historians.

Cartier-Bresson nominated Riboud to join Magnum, the photo collective he helped found, in 1953. Riboud travelled and photographed for the agency constantly until he left to go out on his own in 1979. In 1955, he drove a specially equipped Land Rover to Calcutta from Paris, staying for a year in India. He was also one of the first Westerners to photograph in Communist China, and he spent three months in the Soviet Union in 1960. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s he documented the anticolonial independence movements in Algeria and West Africa, and during the Vietnam War he was among the few able to move easily between the North and South. In the United States, he documented not only protests against the Vietnam War but also a pensive Maureen Dean listening to her husband, the Nixon aide John W. Dean, testify at the Watergate hearings in 1973.

Among the events he documented in recent decades were the return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to Iran; the Solidarity movement in Poland; the trial of Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo chief in Lyon during World War II; the end of apartheid in South Africa; and the mood in the United States before the election of President Obama.

During the last third of his life, Riboud was recognized by museums in many of the countries where he had worked. Photographs from his travels were collected in more than a dozen monographs, including Marc Riboud: Photographs at Home and Abroad (1986), Marc Riboud: Journal (1988), and Marc Riboud in China: Forty Years of Photography (1996). The focus of several prestigious exhibitions, Riboud was honored with shows at the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1964, and the International Center of Photography in New York, in 1975, 1988 and 1997. He was the subject of retrospectives at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1985 and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris in 2004.

Riboud’s weakness for sentimental subjects and left-wing causes marred his reputation with some critics. But this optimism, coupled with his overt sympathies for the downtrodden and a working style that put an emphasis on freedom of movement, unencumbered by any equipment except a camera and his wits, also served to keep him photographing until the end of his life. Until a few years ago, he would begin each day by loading film into his Canon EOS 300.

“My vision of the world is simple,” Riboud said when he was in his 80s. “Tomorrow, each new day, I want to see the city, take new photographs, meet people and wander alone.”

– Adapted from MarcRiboud.com and the artist’s >New York Times obituary