In Conversation: Sabrina Ratté & Deanna Pizzitelli

|

|

|

Deanna Pizzitelli and Sabrina Ratté are two Canadian contemporary artists who, at first glance, are polar opposite in style and sensibility. Deanna (b. 1987) completed a BFA in photography at Ryerson University, followed by an MFA at the University of Arizona. Her practice primarily uses analogue photo printing processes and techniques in the darkroom to achieve handmade prints that are one-of-a-kind treasures. Deanna is also a letterpress artist and fine arts educator.

On the other hand, Sabrina (b. 1982) achieved a BFA and MFA in film production at Concordia University, as well as studying master cinema at Université Paris 8 in France. Sabrina uses computer software to render video and 3D animation-based environments that transport the viewer into another world. Sabrina also creates installations, sculptures, and prints, on top of audio-visual performances.

Both artists are extraordinarily accomplished and produce thoughtful and thought-provoking work. Deanna’s practice is rooted in the creation of an overtly physical object, while Sabrina’s practice almost always involves the creation of a digital environment. And yet, when comparing the work of Deanna and Sabrina, overlapping themes begin to emerge.

We were lucky to be able to have a virtual sit-down with Deanna and Sabrina, to discuss what seem to be apparent overlapping themes and ideas in their work. We hoped to gain a sense of how each artist approaches their work and see to what extent process overlaps. The result was a fascinating conversation that touched on how to represent subjectivities, the use of manipulation of media as a technique to alter ‘reality,’ questions of memory and place, and more.

Moderator: Cassandra Spires

---

Cassie Spires: I kind of get a sense that both of you - in very different ways - represent subjectivities and personal experiences in your work. I was wondering if you can speak to how you balance the representation of objective and subjective realities within your work.

Sabrina Ratté: The idea of subjectivity and how we perceive reality based on our experiences is a fascinating question, and it’s kind of an obsession in my work. The film Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky actually had a big impact on me philosophically. I think it represents the quintessential idea of subjectivity. The characters go into space to discover new worlds, and in the end, they fall back on themselves and reconstruct what they already knew on this new planet. To me Solaris represents how you cannot perceive the world in an objective way. And I think my work is mostly about that. How do we project our subjectivities into the world and in return, how do architecture and virtual environments have an impact on our subjectivities? I also find the ambiguity of reality extremely interesting – how does one know what is real and what is in one’s mind? To reference your question, I don’t know if it’s a balance, but my work is definitely interested in the notion of objectivity, which is a state that’s impossible to reach. I mostly question how we navigate the world with our subjectivities.

Sabrina Ratté: The idea of subjectivity and how we perceive reality based on our experiences is a fascinating question, and it’s kind of an obsession in my work. The film Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky actually had a big impact on me philosophically. I think it represents the quintessential idea of subjectivity. The characters go into space to discover new worlds, and in the end, they fall back on themselves and reconstruct what they already knew on this new planet. To me Solaris represents how you cannot perceive the world in an objective way. And I think my work is mostly about that. How do we project our subjectivities into the world and in return, how do architecture and virtual environments have an impact on our subjectivities? I also find the ambiguity of reality extremely interesting – how does one know what is real and what is in one’s mind? To reference your question, I don’t know if it’s a balance, but my work is definitely interested in the notion of objectivity, which is a state that’s impossible to reach. I mostly question how we navigate the world with our subjectivities.

Deanna Pizzitelli: Hmm. I’m not totally sure! I suppose that objective reality is, for me, a somewhat tenuous term – if we inevitably process things through the filter of our experience, then how exactly do we define objectivity? In my work, more concrete moments in time and space (visiting a new place, connecting with others) are starting points. I may extract a portion of that experience through photography, but then the process of turning that into a photographic print opens it up to all kinds of interpretation and poetry. I’m interested in creating specific representations of emotional landscapes, complex combinations of feeling, and exploring the narrative capacity of an image. For example, you could probably represent longing in a variety of ways, and maybe fairly easily, but could you represent the fantasy of an apology? I’m curious about how detailed you can get with these kinds of subjective representations. I think of my objective experiences as a sort of starting point for digging beyond that.

Deanna Pizzitelli: Hmm. I’m not totally sure! I suppose that objective reality is, for me, a somewhat tenuous term – if we inevitably process things through the filter of our experience, then how exactly do we define objectivity? In my work, more concrete moments in time and space (visiting a new place, connecting with others) are starting points. I may extract a portion of that experience through photography, but then the process of turning that into a photographic print opens it up to all kinds of interpretation and poetry. I’m interested in creating specific representations of emotional landscapes, complex combinations of feeling, and exploring the narrative capacity of an image. For example, you could probably represent longing in a variety of ways, and maybe fairly easily, but could you represent the fantasy of an apology? I’m curious about how detailed you can get with these kinds of subjective representations. I think of my objective experiences as a sort of starting point for digging beyond that.

Cassie: How does digitally or manually manipulating a media affect the representation of reality within your work?

Deanna: A huge part of my practice is very much about manual and analogue manipulation – the darkroom process and the interpretive freedom that one can experience and explore there. That’s the way that I bring my work into the emotional landscape. I also do so in the way that I shoot, but only to a certain degree. The kinds of adjustments I make in the darkroom are meant to direct us towards that emotional space, and away from any kind of singular or objective narrative. When I was younger and first discovering photography, I actually had this idea that the perfect job for me would be to work for photographers in the darkroom as their analogue printer. I really didn’t identify with the shooting process, and - maybe this is too literal of an interpretation - for me it’s the shooting process that has more of that direct link with reality. But then as time went by, I started to engage the shooting process more, and I started to realize that I am both a shooter and a printer, and to understand the peculiarities of both. But generally, the act of being in the darkroom is the departure, and it’s where a lot of the creation happens.

Sabrina: My background is in film production. I studied at Concordia, which was very focused on experimental films. But then I moved from film to video, and I started working with analogue tools like video synthesizers and video feedback - you know, just pointing the camera in front of the TV screen and playing with this for hours - it was a revelation for me. I was also shooting real images, which I don’t do anymore, with my very small camera, and then I would transform that with feedback. For example, I used a landscape in Italy that I shot while I was travelling there, and then transformed it electronically. So that was a manipulation of reality in some ways. Now my work is all produced by video synthesizers and 3D animation techniques. I’ve never painted in my life and I don’t know how to paint, but I really like the idea that I’m painting with light.

Sabrina: My background is in film production. I studied at Concordia, which was very focused on experimental films. But then I moved from film to video, and I started working with analogue tools like video synthesizers and video feedback - you know, just pointing the camera in front of the TV screen and playing with this for hours - it was a revelation for me. I was also shooting real images, which I don’t do anymore, with my very small camera, and then I would transform that with feedback. For example, I used a landscape in Italy that I shot while I was travelling there, and then transformed it electronically. So that was a manipulation of reality in some ways. Now my work is all produced by video synthesizers and 3D animation techniques. I’ve never painted in my life and I don’t know how to paint, but I really like the idea that I’m painting with light.

Deanna: Me too.

Sabrina: There’s this idea of manipulating light, sculpting light, painting with light, transforming it. And to me digital and analogue technologies are ways to work with electricity, which is this impalpable kind of material that you only can access through a computer, or through an interface to manipulate it. So it’s kind of like having access to this impossible world. I think right now I am mostly creating reality, versus affecting it.

Cassie: How does or doesn’t your practice explore ideas of memory, including subjectivity and unreliable memories? And do you have any recent examples?

Sabrina: One of my first videos was called Activated Memory, and I really liked that video actually, but it’s really far from what I’m doing now. I was using photographs of parks in Montreal, and to me these were like idealized realities. These spaces had been transformed, organized and controlled by humans, in order to create what they had in mind as the ‘perfect’ nature. So it’s a video about the idealization of memories, of nature, and how humans want to create this perfect, impossible world. You can find these ideas in my work nowadays, but I haven’t worked explicitly with the idea of memory. Although I’m really fascinated by Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious, and all these memories that we might have subconsciously.

Deanna: Well as a medium, photography is so connected to memory. My work often has this aesthetic of decay, which you could also say is kind of an aesthetic rooted in memory. It looks like it relates to memory in many ways, because my photographs are often faded, and I’m using expired papers, and I’m using analogue and historical technologies. There is a question of time – when the picture is.

Deanna: Well as a medium, photography is so connected to memory. My work often has this aesthetic of decay, which you could also say is kind of an aesthetic rooted in memory. It looks like it relates to memory in many ways, because my photographs are often faded, and I’m using expired papers, and I’m using analogue and historical technologies. There is a question of time – when the picture is.

And in my work, I do collapse multiple geographies and timeframes. My current project, Koža Women and Other Stories, has been unfolding over the last 5 years – it began when I moved to Slovakia in 2015. And it is very much a poetic expression of these years; an unfolding narrative of my experiences. So there is indeed a direct relationship to time, and thus memory. Yet when I think about what the most important aspect of the project is to me, it isn’t its relationship to memory, but rather the evocation of emotional narratives that may or may not reference time. Perhaps regret, for example, is an emotion that references time more directly. But, for me, desire often has the urgency of right now. So I’m primarily interested in the nature of feeling and the ways in which photography can be a vessel for its exploration.

Cassie: I’m wondering how you construct a sense of place in your work, and how does the process drive the outcome of your work?

Sabrina: I guess all of my work is about places. About psychological spaces, architecture, or virtual environments that represent both utopian and dystopian visions. Sometimes my work is also about existing places, like my project called Machine for Living, which was about the suburbs of Paris and their brutalist architecture. Other times it’s about an imaginary place, or impossible space. But mostly, I think what I’m inspired by, maybe more than actual architecture, is the atmosphere, the ambience of a space. How does this affect the way we experience a moment? All this brutalist architecture that I visited had such a strong impact, and with video I often try to recreate this very hard-to-describe emotion that you feel inside of a space. I think that’s a subject in itself that is really rich because these abstract emotions are easy to forget. When I recall some memories, I remember some kind of colour, an ambience, but it’s hard to describe, and I think it’s a beautiful thing to try to achieve through images. This also relates back to subjectivity, because the same space doesn’t evoke the same emotions in another person. So the outcome of my work is trying to translate the impressions inside of a space, and hopefully I can convey some ambience or abstract emotions through the space I create.

Sabrina: I guess all of my work is about places. About psychological spaces, architecture, or virtual environments that represent both utopian and dystopian visions. Sometimes my work is also about existing places, like my project called Machine for Living, which was about the suburbs of Paris and their brutalist architecture. Other times it’s about an imaginary place, or impossible space. But mostly, I think what I’m inspired by, maybe more than actual architecture, is the atmosphere, the ambience of a space. How does this affect the way we experience a moment? All this brutalist architecture that I visited had such a strong impact, and with video I often try to recreate this very hard-to-describe emotion that you feel inside of a space. I think that’s a subject in itself that is really rich because these abstract emotions are easy to forget. When I recall some memories, I remember some kind of colour, an ambience, but it’s hard to describe, and I think it’s a beautiful thing to try to achieve through images. This also relates back to subjectivity, because the same space doesn’t evoke the same emotions in another person. So the outcome of my work is trying to translate the impressions inside of a space, and hopefully I can convey some ambience or abstract emotions through the space I create.

Deanna: When I talk about my process, I often talk about place as a catalyst for new work. Although my most recent project is connected to Slovakia (moving there was the catalyst for this project and changed my life in a variety of ways), I think the sense of place is quite vague in my work. In a way it’s like ‘anti-placeness’ because I sort of try to be unspecific. And so while I’m so grateful for the opportunity to have travelled abroad, and the opportunities for photographing that that has offered me, my images are meant to point to inscapes, rather than specific external landscapes. Places in one’s mind. I think if my photographs are situated in any place, it’s the piece of paper itself. My work is very much about an object that you can hang on the wall or hold in your hands. And this also relates a bit to memory, because my images tend to be small, and it’s reminiscent of the way that we used to experience photography. My mom has recipe boxes full of photos. And when I come across them I always go through them, and it’s very much about the physical way we experience photographs, their sense of touch and texture. So I would say if there is a repeated sense of place, outside of the conversation I’m having right now with Slovakia in particular, it’s the piece of paper itself. But otherwise, I think my work very much pivots away from the idea of (external) place.

Deanna: When I talk about my process, I often talk about place as a catalyst for new work. Although my most recent project is connected to Slovakia (moving there was the catalyst for this project and changed my life in a variety of ways), I think the sense of place is quite vague in my work. In a way it’s like ‘anti-placeness’ because I sort of try to be unspecific. And so while I’m so grateful for the opportunity to have travelled abroad, and the opportunities for photographing that that has offered me, my images are meant to point to inscapes, rather than specific external landscapes. Places in one’s mind. I think if my photographs are situated in any place, it’s the piece of paper itself. My work is very much about an object that you can hang on the wall or hold in your hands. And this also relates a bit to memory, because my images tend to be small, and it’s reminiscent of the way that we used to experience photography. My mom has recipe boxes full of photos. And when I come across them I always go through them, and it’s very much about the physical way we experience photographs, their sense of touch and texture. So I would say if there is a repeated sense of place, outside of the conversation I’m having right now with Slovakia in particular, it’s the piece of paper itself. But otherwise, I think my work very much pivots away from the idea of (external) place.

Cassie: Both of you have a wide variety of skills and techniques in your practices, and I’m wondering how you go about honing a new technique - either a new digital tool, or a new manual process - and how do you then incorporate them into your practices?

Sabrina: I guess what characterizes my work is that it evolves a lot, and I do integrate different techniques constantly. And it’s interesting because I’m not at all a technical person, and I struggle a lot learning new techniques. But I think there’s something about being an amateur with a new technique that opens up so many more possibilities in the sense that you appropriate those tools, sometimes very complicated tools, in a bit of a naïve way, and so you discover techniques that are not meant to be used that way. When I first started, I was working with video synthesizers, which are like old technologies of video that convey a sense of nostalgia, because they remind you of the TV in the eighties, for example. It’s beautiful, but it’s something that I wanted to get away from, because it was too charged with this nostalgic kind of feeling. I was also more and more into architecture, and I wanted to create 3D spaces. So I had to integrate 3D animation, which was a whole new world, and I am still learning, and still doing tutorials after like five years of working with it, and I feel like I’m an amateur, but it’s really great because my vocabulary has been very much enriched by these new tools. And I can mix these techniques. 3D animation I find sometimes a bit too clean, so I try to transform it through other tools. And more recently I have been learning 3D scanning techniques. It’s like 360° photos that you put into a software that interprets them into a 3D model. I am now working with integrating humans in my environments. I must say, even though it’s extremely difficult to learn all these techniques because it’s not natural for me, I do find that I like learning in my work; it really brings it to new levels. My work started with video, but then it expanded into video installation, prints, performances, and 3D sculptures. The heart of my projects is always video, but I sometimes let it emerge in some other forms.

Sabrina: I guess what characterizes my work is that it evolves a lot, and I do integrate different techniques constantly. And it’s interesting because I’m not at all a technical person, and I struggle a lot learning new techniques. But I think there’s something about being an amateur with a new technique that opens up so many more possibilities in the sense that you appropriate those tools, sometimes very complicated tools, in a bit of a naïve way, and so you discover techniques that are not meant to be used that way. When I first started, I was working with video synthesizers, which are like old technologies of video that convey a sense of nostalgia, because they remind you of the TV in the eighties, for example. It’s beautiful, but it’s something that I wanted to get away from, because it was too charged with this nostalgic kind of feeling. I was also more and more into architecture, and I wanted to create 3D spaces. So I had to integrate 3D animation, which was a whole new world, and I am still learning, and still doing tutorials after like five years of working with it, and I feel like I’m an amateur, but it’s really great because my vocabulary has been very much enriched by these new tools. And I can mix these techniques. 3D animation I find sometimes a bit too clean, so I try to transform it through other tools. And more recently I have been learning 3D scanning techniques. It’s like 360° photos that you put into a software that interprets them into a 3D model. I am now working with integrating humans in my environments. I must say, even though it’s extremely difficult to learn all these techniques because it’s not natural for me, I do find that I like learning in my work; it really brings it to new levels. My work started with video, but then it expanded into video installation, prints, performances, and 3D sculptures. The heart of my projects is always video, but I sometimes let it emerge in some other forms.

Deanna: I think I would echo some of the things that Sabrina said. As process-oriented as I am, I sometimes struggle a bit with finding new techniques. The darkroom has, for a long time, been a space where I hold a lot of confidence. I have a connection with a few analogue technologies that feel familiar to me, and this familiarity gives me the confidence to experiment in that space and discover new approaches and nuances within it. When I got to grad school, I really wanted to try working with colour. It had been so long, and the idea of not knowing how to do that bothered me. And so I really switched gears and I was working primarily with large-format colour slide film, which is of course its own unique process. I still had that analogue kind of approach, but I was very much thinking about being a shooter, and not being a printer. And then I reverted back to my old style, but it was with a freshness, and it was with a sense of authenticity, because I didn’t have to do that, but I wanted to.

Deanna: I think I would echo some of the things that Sabrina said. As process-oriented as I am, I sometimes struggle a bit with finding new techniques. The darkroom has, for a long time, been a space where I hold a lot of confidence. I have a connection with a few analogue technologies that feel familiar to me, and this familiarity gives me the confidence to experiment in that space and discover new approaches and nuances within it. When I got to grad school, I really wanted to try working with colour. It had been so long, and the idea of not knowing how to do that bothered me. And so I really switched gears and I was working primarily with large-format colour slide film, which is of course its own unique process. I still had that analogue kind of approach, but I was very much thinking about being a shooter, and not being a printer. And then I reverted back to my old style, but it was with a freshness, and it was with a sense of authenticity, because I didn’t have to do that, but I wanted to.

Skills I’m still working on – installation. For a while now I’ve felt that I wanted to be more adventurous with the way in which I frame and install photographs, and also with how I might introduce other disciplines alongside photography. I’m in the early stages of that, but I think it will be a meaningful direction for me. I also think technical skills can come through collaboration. For example, my partner, he’s also an artist, and he studied photography, but I’ve always seen him as one of those people that just knows how to do a lot of different things. He’s a woodworker, and he builds frames for my shows. But, because of the way that we interact together, I feel like we’ve expanded our technical skills together. I really don’t know how to woodwork, but right now I’m oiling frames, and I’m sanding them, and I’m doing stuff I never would normally do. You know, so it’s coming about slowly, but I feel like there is a sort of technical growth that comes through collaboration. I’m also actually a letterpress artist, so I do some work in printmaking. These kinds of experiments don’t necessarily show in the final stages of a work (they aren’t necessarily visible to an audience), but are often part of the creative process, and help me to reach something I feel good or excited about.

Cassie: You both have already kind of touched on this, but I am wondering what you each are working on now, and does it connect with any of the themes that we’ve been talking about?

Sabrina: Like I mentioned it before, I’m learning 3D scans. It’s a very interesting process to physically exist in my work, because now I’m exploring the body, using my own as raw material that I transform and recontextualize. I’m really inspired by Donna J. Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. I’m into this question of cyborg, how it mixes different identities, the natural and the artificial. I’m also reading some Greek mythologies, learning about goddesses and I’m really drawn into the history of women since antiquity, what it meant to be a woman through the ages. So that’s what I’m working on right now, and it’s very challenging, it’s a completely new direction.

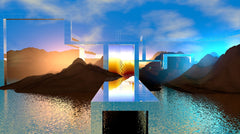

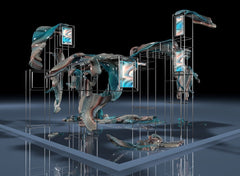

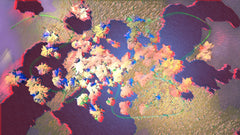

"MONADE I", 2020, by Sabrina Ratté

"MONADE I", 2020, by Sabrina Ratté

Deanna: Right now I’m wrapping up my current project – Koža, Women & Other Stories. It’s been my longest running body of work, and it’s coming to a natural close. So I’m looking forward to seeing that through. I’m not totally sure what the next step is, but I’m ready to move into new directions – to work differently for a while. I can’t say with any certainty what that will look like right now. I did a residency, it was about a year ago now, in Finland, and I was actually working with an 8 x 10 camera, doing a lot of landscapes, and just exploring the countryside a bit. I was just kind of alone and working by myself, and I was thinking about this idea of silence, and what does it tell us about the nature of words? It seemed like an avenue for me and I was working on it a little bit here and there, but really I’ve been engaged with finishing up my main project. So I don’t know what if anything will come of it, or if it’s just part of a larger archive that I will revisit later. But I definitely know that I’m ready. It’s just time to start something new – I’m ready to start thinking in a different way.

Sabrina: It’s a good place to be. It’s a nice place to be.

Cassie: Is there anything that either of you would like to add about your practice, or anything else that you would like readers to know?

Sabrina: I think everybody goes through some kind of process that is a process of creating, and there are a lot of things similar and in common, and I love talking with other artists about their process.

---

Deanna Pizzitelli is one of 11 artists recently presented with Les Rencontres d'Arles' LOUIS ROEDERER DISCOVERY AWARD 2020, which will include an exhibition in November. She is represented by Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto.

Sabrina Ratté is one of 25 recipients of the expanded 2020 Sobey Art Awards. She is represented by ELLEPHANT, Montreal.

Interviewer Cassandra Spires holds a BA in art history from Queen's University, and is currently an MA candidate in Ryerson's Photo Preservation and Collections Management program. Her current research interests include Canadian photography and decolonial practices in public institutions.

"MONADE I", 2020, by Sabrina Ratté

"MONADE I", 2020, by Sabrina Ratté