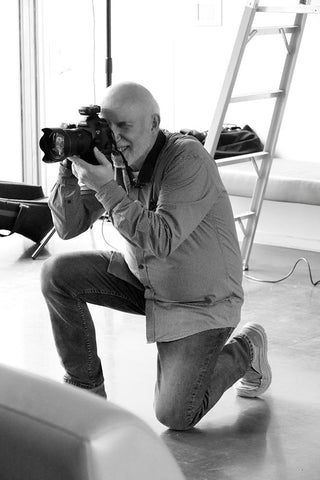

In Conversation: Chris Thomaidis

We welcomed Chris Thomaidis to our roster of FFOTO Exclusive artists after discovering his refined artistic sensibility and ongoing curiosity for where the camera might lead him. His successful career as a commercial photographer complemented a dedicated, parallel fine-art practice that he has come to make his creative priority in recent years. I met with Chris (via Zoom, of course) to talk about his art practice. We covered a lot of territory – from discussing how Chris found his way to becoming an artist, his time as a commercial photographer and how that honed his observational skills, artistic inspirations, and more.

Craig D’Arville: Hello Chris; thanks for your time today. Let's jump right into this. In my research I learned that your first artistic mentor was a painter who liked to remind you that what you exclude from an image is as important as what you include. That sounds like especially good advice to give a budding photographer.

Chris Thomaidis: That would have been in 1977. I was 24. I was at loose ends. I wanted to go to architecture school, but I never did because I’d spent some time in an architect's office and decided it wasn't for me. And so the painter, Libby Davidson, invited me up to stay with them. Libby’s husband Bob was starting a business, a landscape business, actually, something more physical and outdoorsy. I wasn't really keen on photography at the time, it was sort of a passing thing. The Davidsons had a framing store in Toronto, but closed it up to move to Lake Simcoe, where I ended up for a time.

I lived with them from about March to November; came back to the city rarely. Libby encouraged me to use a single-lens-reflex camera that they had. We’d go out – they had a cottage in Muskoka – I would go into their 40 acres of forest, and so I started taking photographs. As I was taking pictures, Bob would develop the negatives, the black-and-white negatives, and I got into that bit. Libby was encouraging but very critical. She would always say, “Well, why don’t you put that in there? Why don’t you include that?” And I would always come back with, “I didn’t even see that.” And so that kind of instruction really set me up for the upcoming bit of life that I had to go through, which was: Now what do I do after I come back to the city?

CD: And you’re still about 24 years old.

CT: I was 24. I came into photography late. A friend had opened a clothing store at No. 1 Yorkville, called Mr. Casual and Company, and she invited me to hang around and be a salesperson. I quickly discovered a whole bunch of things that really helped me: Britnell Book Shop was across the street, so I would go there, as was the reference library, so most of my free time was spent there. And then I discovered Déjà vu Gallery of Photographic Art around the corner and started being influenced by other people’s work through books and that gallery.

Serviceberry, 2020

CD: So this was you educating yourself in a self-guided way.

CT: Yeah; and then somebody at Déjà vu asked me, “Well, do you ever go over to David Mirvish’s place? They’ve got a lot of great photo books.” And that was my Sunday afternoon for the next 15 years. And that’s the way I did it because it’s hard to believe, but I did not know that you could go to school for photography.

CD: So how did that transition into you becoming a career photographer?

CT: Another friend who was an audio-visual producer told me he liked my photographs and asked me if I wanted a job and put me in touch with a small production company. There I made graphics for audio-visual firms and print companies; things like that. By about 1981 I had joined a different multimedia production company with a really good client base that allowed me to focus on photography. My freelance business started to take off. And in all that, I also had a stock photo representation; the whole commercial end of it. But all through that I was still doing my own thing, for me. And that personal work I kept putting aside, but the core always came back to what I was doing at Libby’s, which was surrounded by nature. Until I discovered the work of Stephen Shore and a few other people whose work really impressed me, I’d always stuck to that natural element.

That said, most of my work for companies was a mix of portraiture and still life, so I became proficient at both. And then it all ended because Getty came along. In about 1992 Getty bought Tony Stone Agency, the London-based company that I worked with. And all of a sudden I was making an income from my stock -- far greater than what I was earning from assignments. So, all of a sudden I thought to myself: That’s three kids at home; I can have a portfolio and run around town, or I can concentrate on stock. And so, for ten years I did stock. That freed me up to do a lot of my own personal work. Between the two pursuits it took me about a decade and a half to understand the kind of photographer that I am.

Tulips No. 3, 2020

CD: So all those elements -- making commercial images, stock photographs, and your personal practice -- all combined to develop the sensibility we see in the artworks you make today.

CT: My pictures are very graphic. They always have been, I've been told that by virtually everyone I've worked with. And often, the reasons they would hire me was that, "We really like your graphic approach to image taking."

Charlie Holland, my editor at Getty told me, "You don't make pictures, you take them. Right?" And I thought, "Well, hold on a sec. I make pictures. Everything I do for Getty is a photo illustration of the stuff that sells." She's going, "No. No, but you're still just taking them. You see, there's a naturalness to your pictures that doesn't seem as though they've been contrived or composed in any way. They just seem to ‘Be.’" And so I started developing this approach where it comes back to exclusion.

I started thinking about how things have to be simple. They can't be too complicated. And that's the way I approach pretty much everything I like to photograph.

CD: Your artworks that collectors can purchase via FFOTO have an introspective, observational sensibility. They straddle a kind-of documentary/fine-art hybrid. Let’s talk about that aspect of your work.

CT: I don't know if this is true or not, but I've been told that my pictures are lonely. Photography is a lonely thing. It's very introspective, and you bring that to your work. I hadn't recognized the loneliness until it was mentioned. And then when I actually started thinking about it, yeah, I bring it even to my still life, like you've just said, and see that in the works presented at FFOTO -- simple observations of frozen material in our garden that set off this idea that there’s something beautiful in that. There’s decay in it and, I don’t know any other way of saying it, other than there’s loneliness.

CD: Perhaps thinking of your work as having a sense of solitude, rather than loneliness, is a better descriptor.

CT: Yes, solitude is a better word. The ice things came from reading an article about how the world is changing -- the environment of the world is changing -- because of COVID lockdown, and the planes aren't flying, pollution is falling, and all these other things. I read that and thought: How do I represent that idea, since I can't go to these places to photograph? How do I represent that idea with what I have available?

Japanese Maple No. 3, 2020

Japanese Maple No. 3, 2020

CD: So the ice works from series like Winter Garden are your reaction to making art in lockdown?

CT: Well, I started that series four years ago. And then I went back to it just before I did the ice things. And then I started doing the ice things. It was, again, my experimental thing. I never really knew what I was going to come up with when I was doing them. And then when I saw about three or four of them, I said, “There's something here that feels exactly how I'm feeling right now about our world and our environment.” There's a sense that they don't scream climate change, or any of that. That was my approach to them. And then that thing that I do with most of my pictures where I try to bring a sense of beauty into them.

CD: Your still life photographs have an immediacy to them, partly because they have little depth-of-field. You’re making a more conceptual still life, right?

CT: Most of my still life works are very flat, and there's not a lot of depth, but there's a lot going on. I don’t do it intentionally; I think I just do it intuitively. If I had come down at a different angle and added more depth, it wouldn’t have appealed to me at all. The second I see the way I like it, that’s the way I approach the whole project.

In retrospect, I can look back and say, I’ve always had this sensibility of being drawn to clean, simple, graphic ... anything; architecture, furniture, art, all of that. And that's why even my natural photographs share that graphic feel.

Ice No. 4, 2020

Ice No. 4, 2020

CD: But you don’t stick just to one approach to making photographs.

CT: We live in Scarborough, and I’ve been doing a lot of walks along the Scarborough Bluffs. So, I started working on surf things, and I thought, “There’s something going on here.” And what I realized while I was doing it, without any idea of approaching it technically -- I didn’t bring any of my commercial, technical expertise into these photographs. And I realized, “Oh, I should have cared about depth. I should have done this, or that.” And then I started thinking, “No, the feel of these pictures is because I didn’t follow any of those intuitive rules.”

CD: Is all your work now digital? Do you work with film at all?

CT: I'm all digital, because back in 2005 all my film gear was stolen out of the studio. And I was starting to shoot digital for commercial work, although I still shot a little bit of film. At that time I thought, “Well, am I going to replace all the film work or is everything going digital?” So I went digital. And I didn’t really enjoy darkroom work. I worked with Kodachrome pretty much exclusively for my personal work through my early days.

CD: You’d mentioned Stephen Shore earlier; are there other artists whose work you find to be inspirational?

CT: Minor White, who was a black-and-white guy, was important. That was stuff I was interested in. That led me to Edward Weston, and photographers working in his time. And then Eggleston for colour work. I remember going to Florida on a bus with a friend, just before I started commercial work. We drove somebody’s car back, and everywhere I looked I saw Stephen Shore pictures. I tried to emulate that; it didn’t work. That whole group of photographers were really a strong influence for me going to colour and sticking with colour, and then some more commercial artwork later on in terms of classic commercial work, like Irving Penn.

Hosta No. 1, 2020

Hosta No. 1, 2020

CD: I can see the graphic influence of Irving Penn on your photographs, and Minor White in the black-and-white photographs of the hosta leaves, for sure.

CT: Those are actually colour photographs.

CD: The hostas are in colour?

CT: I flat-sprayed everything black to get the effect.

CD: By the way, your works have terrific price-points. A collector would be wise to choose the pair of those hosta prints to hang side-by-side.

CT: Well, I hope so.

CD: And it sounds like you’ve kept Libby’s advice in your head when making that decision to be experimental with the hostas.

CT: Nobody was a bigger critic about my work than Libby. Libby was just brutal, but a bohemian brutal. It was her personality but really, really sincere, too. And I keep coming back to her, because she was much older; we didn’t have any kind of relationship other than that we were friends. But I learned so much from just being around her, and I think that has stuck with me all these years. “Why is that there?” “Why did you do that?”

CD: I like how this chat has come full circle - talking about the importance of mentorship. Any parting thoughts?

CT: For me, I can take pictures all day long. I find myself in this moment of, “What am I going to do now?” And I think most people who have done something for so long struggle with that. I also ask myself, “What do I have to offer?” Or, "What can I do with my photographs that will bring joy and happiness to other people?" Because that idea has stuck in my head as well -- that Keats line, “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever.”

Chris Thomaidis is a FFOTO Exclusive artist. Look for more works by him coming to FFOTO in the months ahead.

Keep tabs on Chris’ daily activities through his Instagram.