Fading Dreams: The Photography of William Eakin

by Bill Clarke

Fading Dream 227, 2009

Time keeps on slippin', slippin', slippin' into the future go the lyrics of a classic rock song, but it's also an apt phrase to keep in mind while considering the work of photographer William Eakin. Time – historical time, as well as geological and ideological time – weighs heavily on his work. Looking at his deceptively simple depictions of mid-century watch faces, bottle caps and re-photographed Polaroids, we are reminded of time's passage, how it not only imprints itself on objects we've produced and discarded, but how its passing also affects us emotionally and physically. As Eakin has stated previously: “... when you make a photograph, you make an image in reaction to yourself ... By extension, you have made a self-portrait.”1

Night Garden 5, 2001

Night Garden 5, 2001

Eakin's photographs are self-portraits in that they reflect his life-long interest in collecting. As a child, he collected everything from stamps and coins to model kits and bottle caps. “Collecting is a joy and a curse,” he says. “I've always liked things, and I like having stuff around, but I do have to work hard not be owned by the objects I own.”

Upon receiving a camera as a youngster, Eakin started photographing his completed model kits. He began accumulating collections of items with the intention of photographing them in the 1980s, and he has certainly become more discerning in what objects get photographed than he was as a child. “An object needs to resonate with me in some way,” he says. “It's partly autobiographical; I need to know how the object functioned in the culture before I attempt to photographically translate its physicality into an image.”

24Hours 2122, 2013

24Hours 2122, 2013

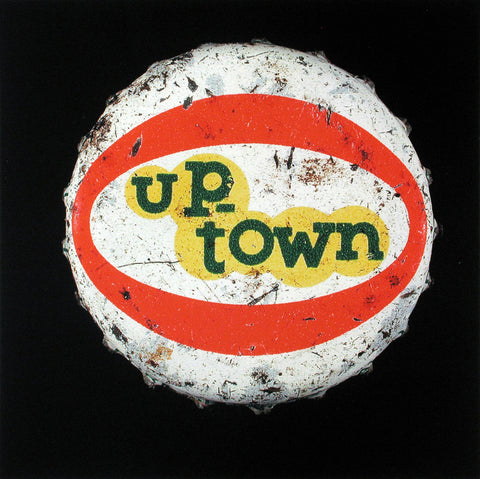

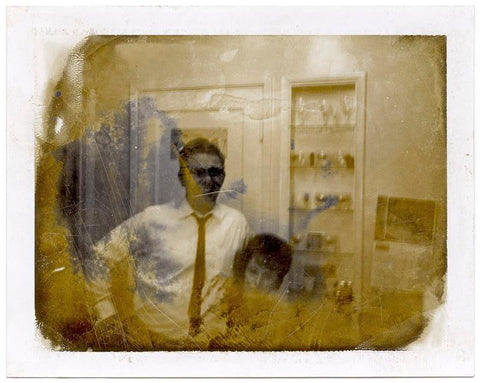

Although now stripped of their original functions, the watch faces of the series “24Hours” (2012), the soft drink and beer caps of “Bottle Caps” and the cookie tins of “Night Garden” (both 2001) at first stir feelings of nostalgia. Rephotographing these objects is, for Eakin, a way to acknowledge and memorialize his parents' era with “affection and gratitude”. The playful Pop Art-y fonts on the Lucky Lager and Up-town soda caps, the jaunty design of a watch face 'signed' by baseball great Mickey Mantle, and the supersaturated colours of the floral cookie tins simultaneously evoke the mid-20th Century's sense of optimism (for some) and the era's repressive (for others) social and political ideologies. Despite their missing hands, dents and patches of rust, once placed before Eakin's camera these humble items become more than mute relics of a bygone age.

Bottle Cap 3312, 2001

Bottle Cap 3312, 2001

“The photograph needs to have its own justification for existence,” explains Eakin. “Otherwise, why not just display the object?” By placing these items in front of his camera, Eakin can zoom in on the patina – the visual traces of time – they have acquired. More importantly, however, Eakin's approach is informed by the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which asks us to seek beauty in imperfection and to accept the transience of all earthly things, ourselves included.

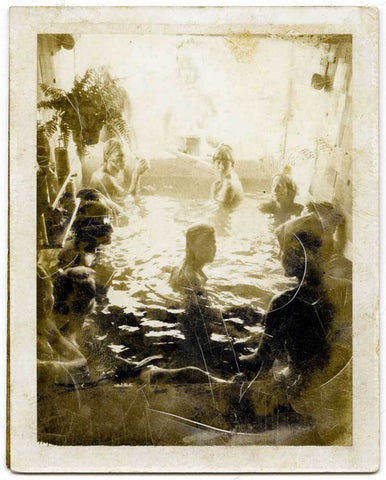

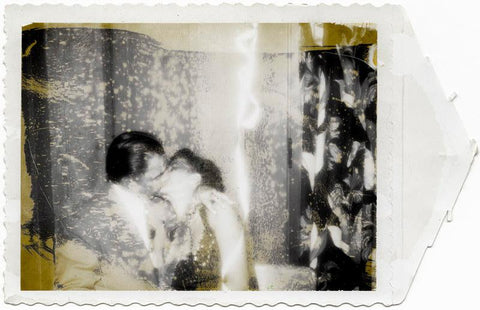

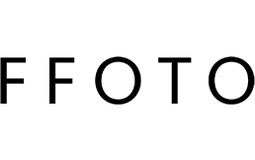

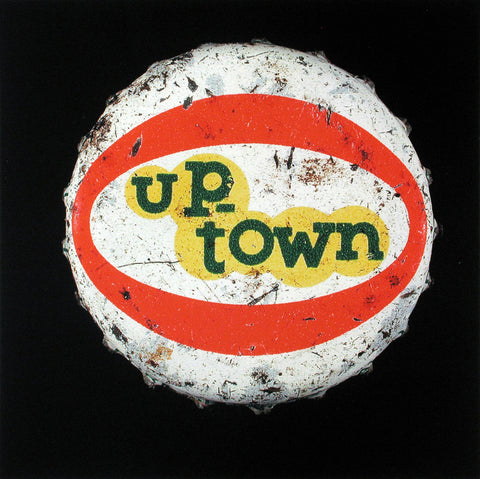

This sense of impermanence is most strongly conveyed in Eakin's work with found Polaroids. The title of the series, “Fading Dream” (2009), links the instability of Polaroid prints – they would fade and discolour if not protected from light – with the changeable nature of our hopes and aspirations. “When I first started working with Polaroid, it permitted me to be spontaneous and respond intuitively,” recalls Eakin. “Like a painter, I could make a mark – a photograph – evaluate it instantly, and make another in response.” For 10 years, until the materials became unavailable, the artist worked with a film that provided a print along with a recoverable negative that could be used to make larger prints. Eventually – perhaps not surprisingly, given his collector's impulse – Eakin began looking for Polaroids at the same rummage shops and garage sales where he'd been finding bottle caps and tins.

Fading Dream 197, 2009

Fading Dream 197, 2009

Old photographs that have become separated from their original owners possess an inherent abjectness. Depicting places that have irrevocably changed, or people who may no longer be alive, such images are coded with the social, political and personal ambitions of their makers and the broader society in which they were living. Similar to his approach with the bottle caps, Eakin's photographic interventions draw our attention to the fragility of the photographs' surfaces, with their creases, discolourations and abrasions. “There is also a talismanic quality to these vintage prints,” he says. “The actual photons that struck the material, so long ago and in many exotic places, remain literally embedded in the print.”

Fading Dream 107, 2009

Fading Dream 107, 2009

Earlier, the word mute was used in reference to Eakin's rephotographed objects, but they are actually far from inexpressive. These humble, easily overlooked items are intended to prompt discussion of contemporary concerns. “The objects I've collected are catalysts for contemporary work that, I hope, is imbued with an understanding of where we've been, and that hints at where we're going,” say Eakin. “It's important and necessary to reflect on the past as we move forward.” Wise words at a time when it seems our world is slippin', slippin', slippin' into an uncertain future.

- Laurence, Robin. Time Play: William Eakin and Remembrance. Canadian Art, Winter 2012.

--

Bill Clarke is a Toronto-based writer who, since 2006, has contributed frequently to national and international publications, including Canadian Art, Border Crossings, Modern Painters, ARTnews and ArtReview. You can spy on him on Instagram at @billseesworld.

Night Garden 5, 2001

Night Garden 5, 2001

Bottle Cap 3312, 2001

Bottle Cap 3312, 2001 Fading Dream 197, 2009

Fading Dream 197, 2009 Fading Dream 107, 2009

Fading Dream 107, 2009